The Invisible Made Visible: Distortion as Truth Telling

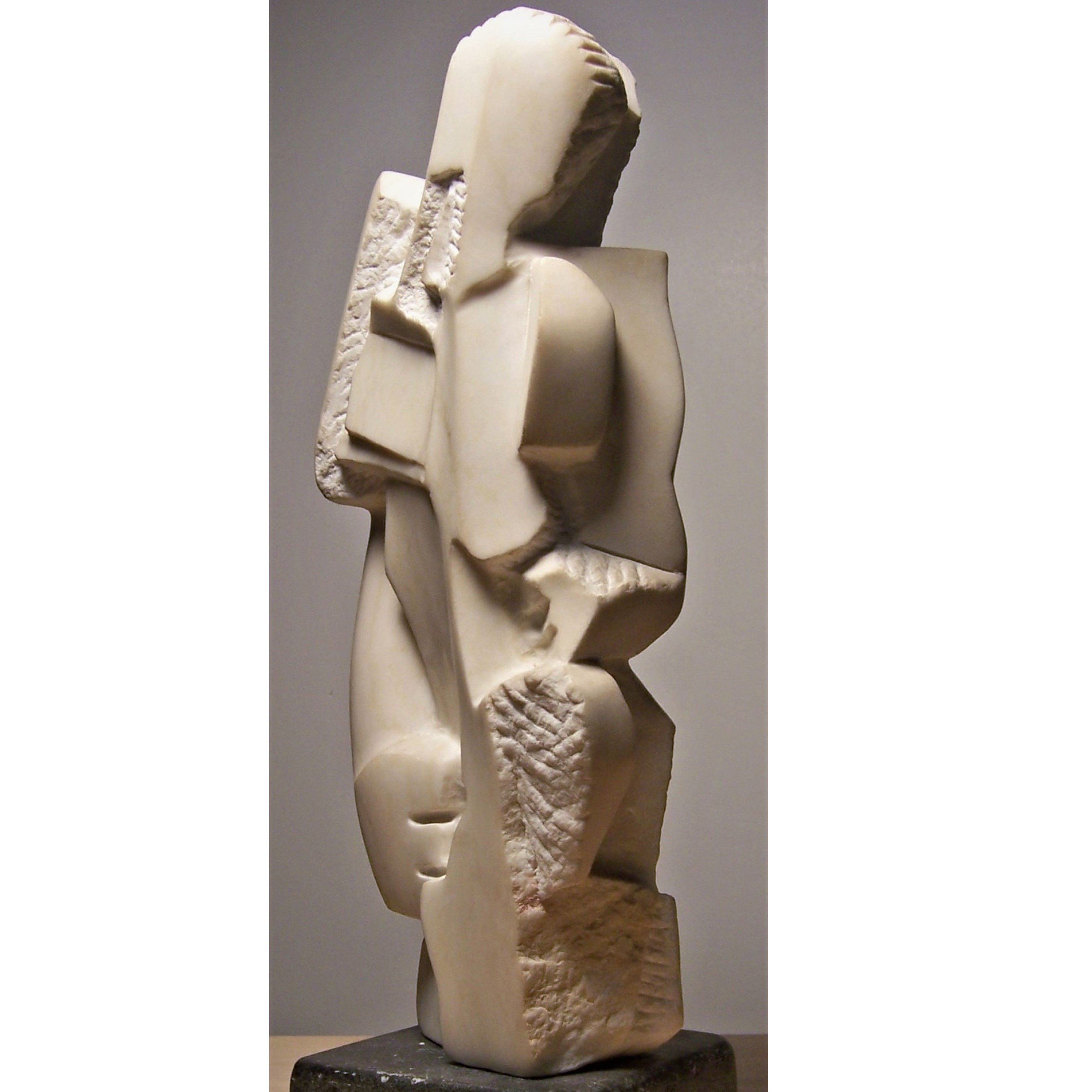

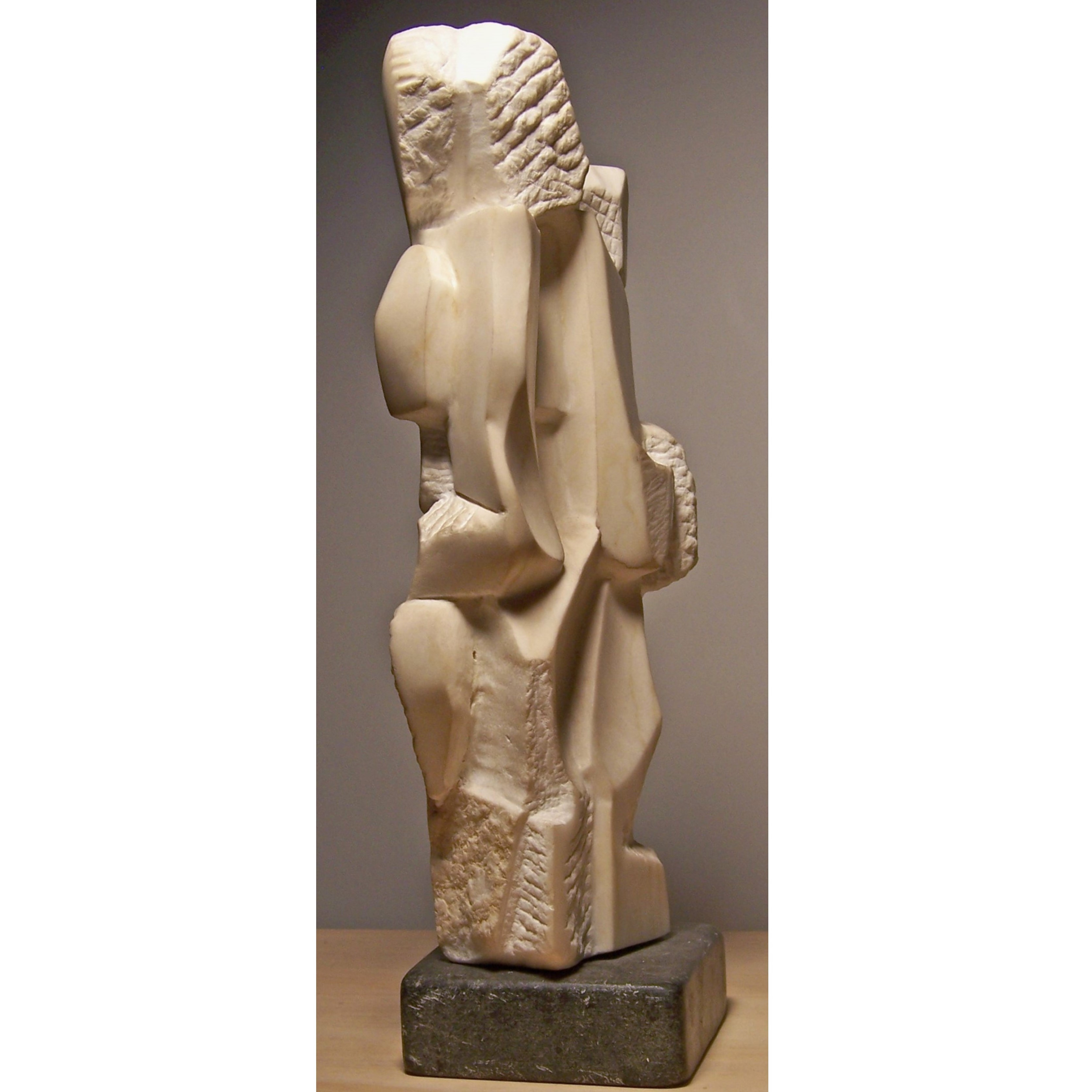

Ellison’s Invisible Man (1952) exposed how Black identity was erased; today, hypervisibility distorts it. My cubist figures that are made with fractured planes and exaggerated limbs. These mirror sociological findings: Black men are 2.5x more likely to be perceived as threatening (Goff, 2014). The stone’s weight literalizes the burden of these projections.

Stone as Skin: How Texture Bears Witness

Chisel marks become scars. The rough texture cites Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks (1952): colonial gaze frames Black bodies as "unfinished." Like unpolished stone, these figures resist respectability politics, and their raw surfaces rebuke respectability’s erasures (Higginbotham, 1993). Every groove holds history.

From Hypervigilance to Healing: Reclaiming the Gaze

Hypermasculinity is a survival reflex. Studies link racial stress to heightened cortisol (Hicken et al., 2013). My figures’ tense postures mirror this biological reality. But just as stone reveals beauty in its fractures, liberation begins when we see Black masculinity not as threat, but as testament to resilience.