Pixels and Pigments: The Evidence We Can't Unsee

The 1991 beating of Rodney King and the 1999 killing of Amadou Diallo who was shot 41 times by NYPD officers, inspired "Black & Blue." My cubist fractures mirror the countless unrecorded brutalities that blur into America’s periphery. Studies confirm Black men are 2.5x more likely to die in police encounters (The Lancet, 2021). The painting’s splintered planes represent both the violence we see and the systemic patterns we overlook. Each shard is a different case file, each angle an unacknowledged tragedy.

The Geometry of Oppression

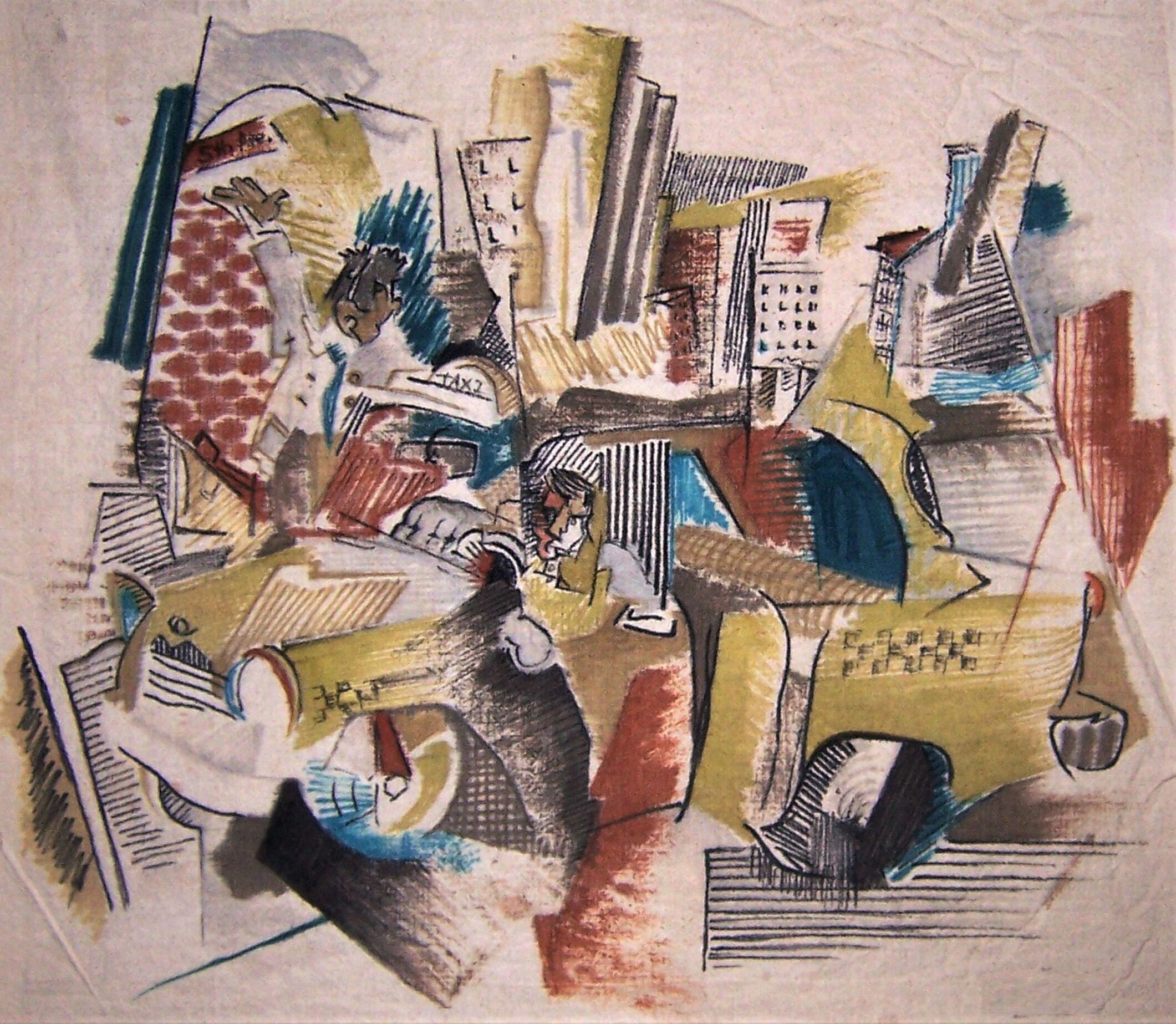

"Can’t Catch a Cab" exposes transportation bias: studies show white passengers enjoy a 60% first-taxi acceptance rate, while Black passengers languish below 20% (NYU, 2017). The artwork’s unbound cityscape, where skyscrapers and sky dissolve into open space. This contrasts sharply with the grounded figure, trapped at the curb. The planes don’t just fragment the scene; they reveal how mobility itself is policed by prejudice.

"The Accused" distorts courtroom angles deliberately

Sentencing Commission data (2022) shows Black men receive 19% longer sentences for similar crimes. The judge’s gavel becomes a guillotine; the jury’s faces merge into one indifferent mass. Cubism, here, is the only honest perspective.

From Cell Blocks to Canvases: The Art of Resistance

""Black Houdini"’s prison-school window isn’t metaphor. It’s math: Black students are 3x more likely to be suspended (DOE, 2021), feeding the school to prison pipeline. The unprimed canvas and chalkboard grey colour harkens the carceral systems’ & classrooms share architects.

The Unity

Yet these paintings intersect like solidarity. Their shared palette with bruise purples and protest yellows serve to reminds us how bias fractures, but art reassembles. As Kimberlé Crenshaw’s intersectionality theory frames it, our struggles converge.

The brushstrokes don’t lie; they link us.